Confederate Monuments Symbolize White Supremacy And Hate

Confederate symbols across the country have come under closer scrutiny in recent years. Indeed, they are the source of contention in many of the recent skirmishes mentioned in the news the last few years.

Before the recent toppling and removal of a select few, there were at least 1,503 monuments or symbols of the failed Confederacy in public spaces around the US. There are another 109 public schools named for its contemptible leaders. The Southern Poverty Law Center collected detailed information on the establishment of each one them [1].

Here is the kicker, nary a single one went up in the years immediately after the Civil War. Nearly all of these symbols came about during two separate periods of US history. The first spanned the 1890s to the 1920s. The second wave began with the tide towards the establishment of civil rights for all, as whites began to feel threatened and fear gave way to hate.

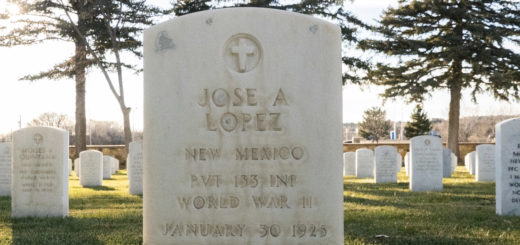

The first period was underpinned by the backlash formed with the slow pace of reconstruction in the south and the resentment that had been stewing in the decades after the war. Demand for recognition and preservation lead to national groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded in Nashville, Tennessee in September 1894) and Sons of Confederate Veterans (founded July 1896 in Richmond, Virginia). With the formation of such groups monument-building reached a fervor in the new century. The mood of the times was eventually stoked by Thomas F. Dixon in his book, The Clansmen: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, in 1905. The film adaptation, D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation in 1915 spread the message like wildfire. This was a period in which many monuments were erected or at least put into the planning and fundraising stages. Another effect was the rebirth of the Klan – a group that had been extinct and written off as far back as the 1870s. The growth of the Klan at this point was rapid, so much so that by the summer of 1924, various national rallies sporting attendance numbers in the hundreds of thousands were held across the nation. Their efforts were to affect the national and local elections of that year. They helped raise funds along the way and more monuments were erected. The statue in Charlottesville that was the focal point of last weekend’s protests was erected in 1924 (having been approved in 1915). This was also a period, coincidentally, that many of the southern Jim Crow laws appeared on the books. The monuments were part of a systematic means of disenfranchising an entire class of people, no doubt about it.

The second wave of establishing Confederate symbols started with the civil rights era, the 1950s through the 1960s. Brown v. Board of Education was 1954. Following that singular event there was a surge in the growth of Confederate symbols and monument building. During this era the focus was not on statues so much as it was on the establishment of schools, the flying of the confederate flag in public spaces, and the creation of Confederate-branded state license plates. If you must desegregate your schools, it only seemed to make sense to reassert your authority through the shaming of students of color by forcing them to attend schools named for one of the failed Confederate sons. This wave of monuments building looks to have died abruptly with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the rising social awareness and protests of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Looking at the time graph in the SPLC study there has been another uptick in Confederate monuments building peaking around the year 2000. It’s time to put it to rest. These are nothing but symbols of hate and oppression and should no longer be tolerated.

The dedication of Confederate monuments and the use of Confederate names and other iconography began shortly after the Civil War ended in 1865. But two distinct periods saw signi cant spikes. The rst began around 1900 as Southern states were enacting Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise African Americans and re-segregate society after several decades of integration that followed Reconstruction. It lasted well into the 1920s, a period that also saw a strong revival of the Ku Klux Klan. The second period began in the mid-1950s and lasted until the late 1960s, the period encompassing the modern civil rights movement.

[1] “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols Of The Confederacy”; Southern Poverty Law Center; April 21, 2016

Recent Comments